Commemorating Communist Rule in Hungary: The Role of History in Times of Democratic Decline

Current political developments in Hungary and the country’s path towards democratic consolidation after the collapse of State Socialism prompt the question of how the past is reinterpreted in Hungarian politics today. How does Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s current Prime Minister, use history to shape the public discourse in his most recent public memorial speeches? Besides gaining knowledge of the past in order to understand the present, it is similarly important to understand its use, its abuse, and the power it has in the public sphere.

By Linda Weigl

Nationalist sentiments and xenophobic, ethnocentric prejudices are gaining popularity across Europe. When considering the situation in present-day Hungary, it is tempting to understand the current government’s self-proclaimed ‘illiberalism’ and hostility towards migrants as just another expression of contemporary political resentment. However, a closer analysis reveals that the nationalist attitudes and practices that have come to the fore under Viktor Orbán’s leadership in Hungary cannot be simply subsumed under a broader European pattern. They have their own origins. Consequently, it is not possible to understand the articulation of Hungarian politics nowadays without grasping the nation’s past.

Hungary, once a one-party socialist republic, had been a promising paradigm of peaceful democratic transition for a long time. Two decades after the fall of the Iron Curtain, liberal democracy had, in most central and east European countries, replaced authoritarianism. The collapse of the communist system and the consolidation of a parliamentary democracy were the result of an accumulation of multiple events and circumstances during the 1980s. In contrast to the early post war years, when the Soviet Union was economically stable and militarily well equipped, the USSR underwent a severe economic crisis in the 1980s. The ailing superpower lagged behind the United States both financially and technologically and could also not keep up with the lure of increasing consumerism that had swept through the West in the 1980s. Gorbachev’s leadership contributed to a relaxation of repression and censorship in many of the satellite states of the Soviet Union. Hungary would profit from the declining success of communist parties and the destabilization of the Soviet regime. In June 1989, the so-called National Round Table started negotiations of the formation of a democratic political system. Censorship was eased, trade unionism legalized, and a multiparty system as well as the separation of powers consolidated. Shortly afterwards, an agreement about the withdrawal of Soviet military forces was signed, which finally led to a democratic government and free elections. In 1999, Hungary joined NATO and, now recognized as a consolidated democracy, became a member state of the European Union in 2004.

Fourteen years later, under Viktor Orbán’s rule, this status as a consolidated democracy has become questionable, since the country is witnessing a process of democratic backsliding. Not only media headlines draw public attention to this case of democratic decline. Also scholars, research institutes and the European Parliament have called for action against the country’s violation of the EU’s fundamental principles and values, all of which confirm that the current leadership is ‘un-consolidating’ Hungary’s young democracy. This political development raises questions about the impact of Hungary’s communist past on politics today. How does Prime Minister Viktor Orbán use history to further his political aims in the public sphere? The answer to this question is of high socio-political relevance. A nation that has just left behind decades of communism and evolved into a fully established democracy is now ruled by a leader who masters the potential of the linkage between an evocative past and a vulnerable present marked by political dissatisfaction and public concerns.

The Use of History through Public Speeches

According to the historian Klas-Göran Karlsson history can be told, explained and used in multiple ways and with different intentions. The existential use of history is perhaps the most neutral and apparent one. Its main purpose is to create, in Karlsson’s words, a “presence of the past” as it helps to furnish a collective memory as well as a personal identity. The ideological instrumentalization of history as it is used by intellectuals and the political elite, serves the exploitation of historical facts to promote a specific ideological cause. Closely linked to this typology is the political-pedagogical portrayal of past events. It is characterized by political decisions that seek to convince the population to spend a certain amount of effort and time engaging with specific historical topics so as to attract public attention to concrete contemporary issues.

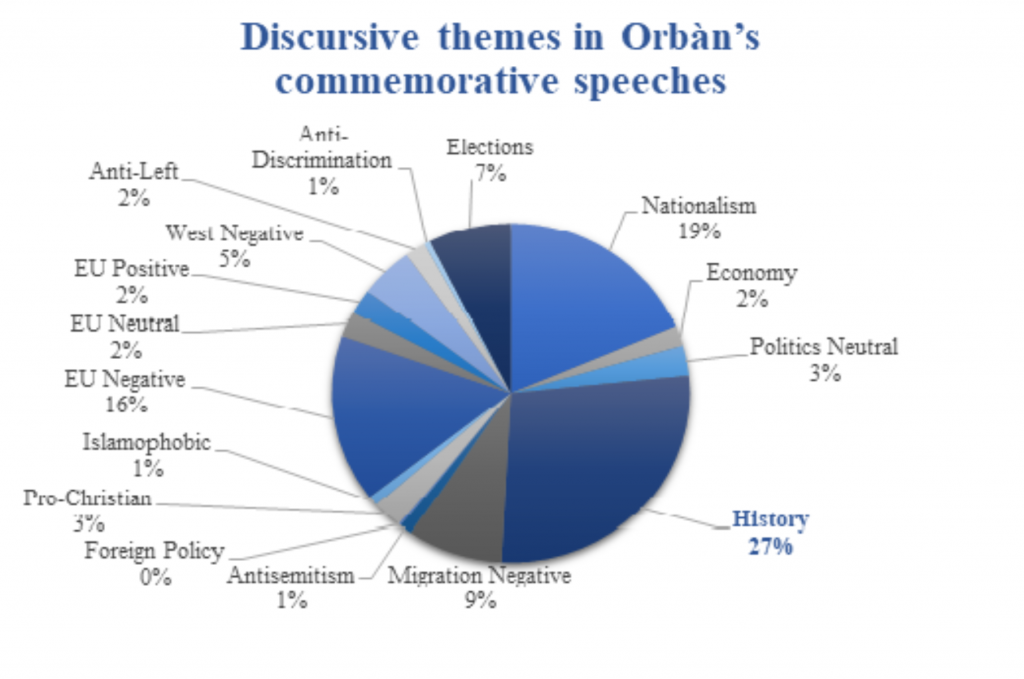

In order to explore how Viktor Orbán is addressing and using the past, this essay analyses six of his most recent memorial speeches. Each sentence of the speeches has been linked to one or more political topics in order to identify common patterns. The discourses were also investigated qualitatively based on the concept of “political framing”. Elisabeth Wehling explains that frames are mental structures which reorganize the way in which we process information. Public speakers often engage in political framing when delivering a message to the masses. All too often, she asserts, framing is used as a manipulative tool. This makes it an interesting rhetorical instrument to be considered when analyzing Orbán’s public statements.

Politicizing Hungarian History

Starting with Viktor Orbán’s speech from 2015 commemorating the victims of communism, a close analysis reveals that 54 percent of this speech are dedicated to the remembrance of the victims. The second largest share, namely 17 percent, expresses strong nationalist sentiments, mirrored by an almost equal share of 15 percent directed against the West. In 2016, on the national holiday of October 23rd, Orbán held a speech in remembrance of the 1956 Hungarian revolution. Barely 40 percent of the text sought to engage with aspects of remembrance. 11 percent of the content criticized the EU and almost 10 percent contained hostility against migrants.

The same event one year later witnessed Orbán delivering a speech that followed a similar pattern, but the share of the memorial content dropped to just 28 percent and nationalist expressions were found in about one fifth of the text. Criticism towards Brussels more than doubled, so that EU-related concerns amounting to almost 24 percent are the most represented arguments of the speech. Furthermore, Orbán expresses, albeit hidden, antisemitic attitudes by repeatedly picking at the allegedly scheming financial networks. His speech also includes some paragraphs devoted to the Hungarian elections in April 2018.

Orbán delivered another commemorative speech at a conference in memory of former German chancellor, Helmut Kohl. Less than ten percent of the speech are actually dedicated to Kohl. About one fifth of it consolidates his Eurosceptic stance and an additional four percent express discontent towards the West. Almost 15 percent of the text are directed against immigrants and an equal share serves the promotion of the European People’s Party for the European Parliament Elections in 2019.

The chart above summarizes the overall share of each of the different categories within all six speeches. This prompts the question of why historical issues, which are the actual subject of those speeches, only occupy 27 percent of them. Since percentage rates are only of limited value in explaining complex issues, it is important to consider the context in greater detail.

“Soviet rule […] sought to destroy both our past and our culture. […] The truth is that now, […] everything that we think about Hungary […] is once again under threat. […] In the twentieth century the trouble was caused by military empires, but now […] it is financial empires which have risen up. […] They are fast, strong and brutal. It is this empire of financial speculation that has captured Brussels and several Member States. Until it regains its sovereignty, it will be impossible to turn Europe in the right direction. It is this empire that saddled us with modern-day mass population movement, with millions of migrants, and with a new migrant invasion. […] We alone resist them now. We have reached the point at which Central Europe is the last migrant-free region in Europe. This is why the struggle for the future of Europe is being concentrated here.” (Orbán, 2017)

This quotation, extracted from a speech given in 2017, shows how Orbán parallels the Soviet empire with today’s financial empires, by which he is referring to the technocratic elite that, in his view, rules in Brussels. To highlight his rhetoric strategy, crucial terms have been emphasized in bold in the quote above. These words, all being related to the concept of ‘war’, bring forth a strong negative connotation. As such, the wording creates the impression that Hungary is being invaded and occupied anew. The word ‘invasion’ triggers concerns about one’s own security and when repeatedly connected with the term ‘migrant’, the ‘migrant invasion’ reshuffles its initial meaning. Immigrants will not only be associated with something ‘new’, but also something ‘massive’ that constitutes a ‘threat’ to one’s own sphere.

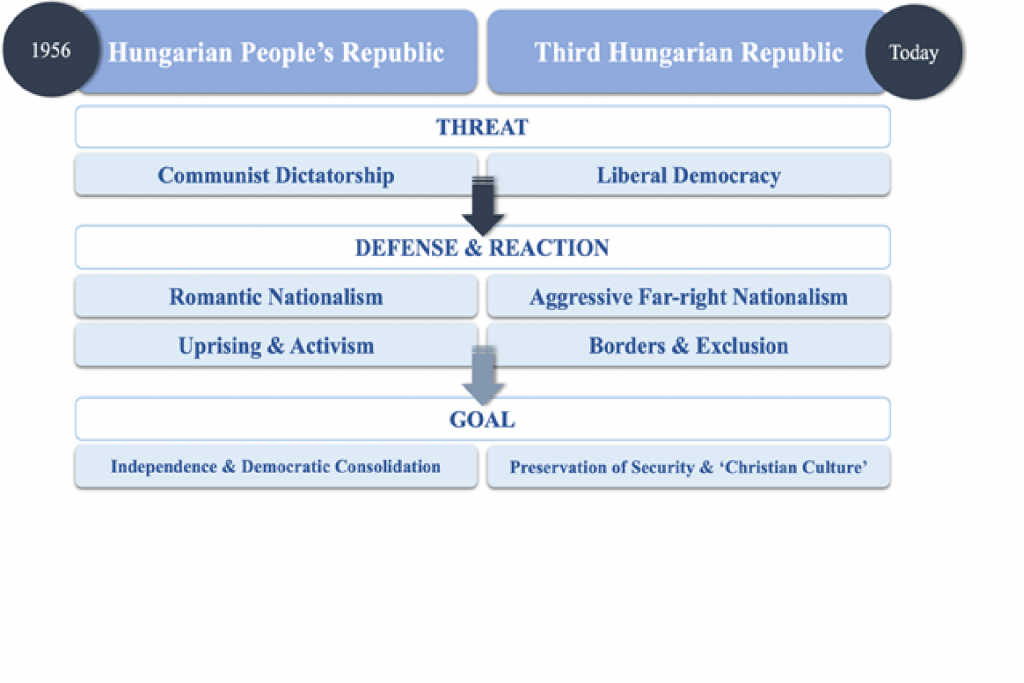

Orbán is not only referring to migrants when he calls for Hungarian resistance. The general pattern that stands out is the parallelizing of two worlds. Thus, he projects the experiences under the communist dictatorship onto today’s reality in which he perceives life in Hungary as being under threat. The flow chart below is a simplified illustration of this strategy.

His allegory, therefore, essentially equates the European Commission, corrupt and unable to protect Hungary, with Moscow. Orbán asserts that while the communists turned the “Hungarians into Homo sovieticus […] the forces of globalism are […] working on turning [them] into Homo brusselius”. Closely linked to this parable, he also stresses that communist theory was originally a Western idea, which was practically forced upon Central and Eastern Europeans. He thereby creates a perpetrator-victim narrative. Thus, in a speech at the inauguration of the Monument to the Victims of Soviet Occupation, he argues that “Europe has been a homeland to […] cataclysmically destructive ideologies like National Socialism [and] international communism […] – all first reared their heads in lands to the west of us.” He goes on claiming that “from time to time the spirit of Marx, Lenin and the re-education camps still emerges in Europe. […] And there are people who want to launch proceedings […] against us, just because we see the world differently […] and because we do not want to become an immigrant country.” He therefore legitimizes his nationalist attitude with the fact that Marxism emerged in western European states, which, according to him, is the root of the suffering experienced by Eastern Europeans living in State Socialist regimes in the second half of the twentieth century.

Left-wing parties and liberally minded politicians, for obvious reasons, strongly oppose Orbán’s radical ideals. He discounts them by linking them to the cruelties committed under Communist dictatorships and claims that “our left-wing and liberal opponents […] want to dictate what we can and cannot talk about. […] For us, the countries that have experienced communism, this brings back bad memories.” By using such discursive formulas, the Prime Minister justifies his right-wing policies, nationalism and border enforcement as a way to “protect” the country and the European Union as a whole. In his eyes, the Hungarians who already stood up against Soviet rule and helped the Germans by opening the ‘green border’ in 1989, have to fulfil their duty by closing the borders to keep refugees from entering the country. According to him, Hungary constitutes the bulwark of Europe, since national bravery and the pursuit of freedom have always been inherent to the Hungarian people.

The national independence that led to the withdrawal of the Soviet empire and greater freedom in Hungary goes hand in hand with Orbán’s nationalistic ideals to resist “the EU’s transformation into a modern-day empire” and “save Brussels from sovietisation”. Accordingly, his speech commemorating the 1956 revolution ends with a direct plea for the Hungarian elections in 2018, in which he calls for contesting the multicultural, liberal order, and the European bureaucrats by regaining national sovereignty.

The Existential, Ideological and Political-Pedagogical Tool

Following Karlsson’s typological framework on the public uses of history, one might argue that the past is used in an existential way in Orbán’s speeches. Hungary has endured more than 40 years of Soviet control, which did not leave the public unscathed. This has to be kept in mind when trying to grasp to what extent the confrontation with the past can be used to persuade Hungarians on a vulnerable personal and emotional level. Next to this existential construction of collective memory, Orbán is engaging with an ideological use of the past. This is done by creating political frames, but also by simply selecting and emphasizing historical events that serve the legitimization of his ideals, while omitting those that might not be in line with his intentions. Third, Hungary’s past is addressed also in a political-pedagogical fashion. Orbán is deliberately stressing a certain point of view on the past in order to educate the population in line with his own moral views. It may be worth mentioning that Orbán’s speech in 2017 in memory of the 1956 Revolution was held in front of the House of Terror. The museum was founded by Orbán himself. It is subject to controversy and criticism, as it is accused of distorting public perception about historical facts by a one-sided portrayal of the past. It is evident that besides knowing the past to understand the present, it is similarly important to understand its use in the public sphere. Clearly, Orbán’s rule in Hungary is witnessing a drift towards authoritarianism, and his use of history as a means to legitimize national sovereignty and hostility towards established elites are indicative of his broader illiberal and exclusionary attitudes.

This development should not be equated with the contemporary success of far-right parties and leaders in other European Member States. In comparison to some of the other countries with a re-emergent Far-Right, Hungary’s democracy emerged out of a long history of popular uprisings and failed revolutions. The very nature of Hungary’s political roots thus has a great impact on the performance and stability of its democratic system. Through public speeches, Hungary’s Prime Minister is seeking to persuade a nation that is exposed to an emotionally evocative and divisive past. He does so by engaging in an ideological and political-pedagogical instrumentalization of history. Citing Karl Marx at this point is perhaps ironic, yet adequate when talking about Hungary’s democratic backlash. Marx famously referred to Hegel’s theory of historic recurrence, which can be interpreted as a possible articulation of Hungary’s history of the last century, and its perception in the contemporary political context. This appears particularly accurate in light of the emerging nationalism and the parallel gradual decline of democracy in Orbán’s government:

“Hegel remarks somewhere that all great, world-historical facts and personages occur, as it were, twice. He has forgotten to add: the first time as tragedy, the second as farce” (Marx, 1852).

Linda Weigl is studying for an MA in European Studies and specializing in European Public Policy and Administration at Maastricht University. In her master’s thesis, she is working on the revision of the EU’s Posting of Workers Directive. Weigl holds a BA in Political Science with a specialization in Politics and Economics from the University of Milan.

This article is a revised version of a paper produced for the course Post-war Europe: Political and Societal Transformations within the MA in European Studies at Maastricht University.

Short bibliography:

Buchanan, T. (2006). Europe’s Troubled Peace 1945 to the Present (2nd ed.) Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Suggested reference

Linda Weigl: Commemorating Communist Rule in Hungary. The Role of History in Times of Democratic Decline. In: RUB Europadialog, 2019. URL: http://rub-europadialog.eu/commemorating-communist-rule-in-hungary-the-role-of-history-in-times-of-democratic-decline (16.05.2019).